“We don’t come to consume but we come to contribute.” A Conversation with a Refugee living on Lesbos

- AISU Editorial

- 24 jan 2021

- 8 minuten om te lezen

Bijgewerkt op: 25 jan 2021

By Corinna Billmaier

“What is Moria? It is where Europe’s ideals - solidarity, human rights, a safe haven for victims of war and violence - dissolve in a tangle of bureaucracy, indifference, and lack of political will. It is the normalization of a humanitarian crisis. It is the moral failure of Europe.” Rachel Donario, Journalist.

The fire in the Greek refugee Camp Moria in September 2020, that left almost 13.000 people without shelter, brought the precarious living situation for people seeking refuge in Europe back into the media and into our minds. Demonstrations were held all over Europe, like this one in Utrecht. Organizations collected material and financial donations and European governments declared they would accept hundreds of children who were travelling without parents. All this gave hope for change in the European migration policy.

4 months later, Moria has disappeared more or less out of people’s minds and the political discussion. Although the Dutch government has by now brought 100 vulnerable refugees from Greece to the Netherlands, among them children and their families, this is not much more than a symbolic gesture. There are still thousands of people left behind, who might not be as vulnerable, but nevertheless deserving of a life in safety and dignity.

Other pressing issues have taken over the news and the saying proves to be true: “out of sight, out of mind.” Current news from refugees and migrants stranded in Bosnia after a fire destroyed camp Lipa, bring to light another hotspot of a European migration policy that fails to provide basic humanitarian standards to those seeking a better life for themselves and their families. For the former inhabitants of camp Moria, the consequences of the fire remain real and present.

For this article I have been in contact with a person who has been living in camp Moria since 2019. He is the founder of the Instagram account the Humans of Moria which is managed by a team of young refugees. They share personal stories, images of everyday life and daily struggles in the refugee camp.

In our conversation he talked about how the situation got even worse in the new camp that has been set up to replace Moria. Ahmad (name changed) said plainly: “If you had to rate it, Moria was 0 out of 10. The new camp is -5 out of 10.” While people were still allowed to leave Moria to go to the nearby city, the new camp is strictly closed off. Leaving the new camp is only possible once a week with a special permit. Ahmad told me about how the opening of the new camp was accompanied by troubles. After sleeping on the streets for 2 weeks until the new camp was set up, many people refused to move in. Instead of being transferred to another camp, where they again would be living under harsh conditions, people protested and demanded freedom and proper accommodation. Protests went on for two weeks but were met with brutal police force and teargas. Only through the threat of the immediate denial of anyone’s asylum procedure who resisted moving into the new camp, protest could be dispersed.

According to Ahmad, sanitary conditions and electricity are even more scarce than they were in Moria. The new camp is located directly at the sea which means it is not shielded from harsh winds. Winter adds to the already precarious situation. In December 2020, after heavy rainfall, floods have made conditions in the tent city even worse. And most of all, the community that had developed in Moria over the years has been disrupted. Ahmad said: “Moria has been there for a long time. People have been setting up everything. They were familiar with the life in the camp. They started little businesses, we were having some restaurants and little shops there.”

With the fire, all this is gone. People had no chance of taking anything with them once the fire started. However, Ahmad also points to a positive outcome of the new camp. He says that here the inhabitants of the tents are grouped by region of origin. In Moria, tensions between different ethnic and religious groups have sometimes risen and led to fights or even killings. With tents being inhabited by people of more or less the same cultural background, conflicts might be avoided. In a camp where nobody is allowed leave, where people are stuck for months or years with no prospect and nothing to do all day, it is questionable though how long this will keep the peace.

Another positive outcome, as Ahmad explains, is the increased presence of police in the camp. In Moria it sometimes happened that people were robbed in their sleep. Because electricity often ran only during the night, residents had to charge their phones while sleeping and this circumstance was abused by others. When I asked whether police isn’t there primarily to supervise the residents and prevent them from leaving the camp illegally, Ahmad negates: “No, because it is closed with high fences and there is no way you can leave the camp.” The only way out is the main entrance, which is guarded.

Due to increased police presence and a new law that bans sharing any information from the new camp, it has become harder for Ahmad and the whole team to take photos and videos to document daily life. The ban applies not only to the camps residents and visitors, but also to international journalists.

Ahmad has a positive outlook on life and is optimistic that things will turn out well for him. His voluntary work as a medical translator in the camps keeps him busy and connects him to a lot of people. For many others, the traumatic experience of fleeing their home country, as well as the subsequent inhumane conditions in the camps, results in serious mental health problems. Depression is common and for some the only way out is suicide.

Ahmad’s message to the European public is clear. He said: “Europeans should be aware that the people in the refugee camps are people, just like them. We aren’t small people. Small people don’t exist, only bad situations for a temporary period because under the sun everything is in movement. We are worth the same and Europeans are not entitled to any nonsense superiority complex. Having been born in Germany, France, the Netherlands or wherever is just a chance and not a miracle. It doesn’t make you superior people. Tomorrow I will do great things, I have commitment and I have a vision. And that’s not only me, but also others.”

He also wants Europeans to know that refugees are not burdens to their societies. “We don’t come to consume but we come to be contributors to the development of our host countries, Europe and our families. We want to integrate, learn the language, increase our skills, work hard, pay our taxes. Even if we left all our possessions behind, we still have energy and commitment to work. We have smart brains, ideas, we are educated. We have hopes and dreams. But in our countries we can’t live in safety or freedom. This is the reason to leave everything behind and get in that extremely risky boat to come here despite all those risks along this horrible journey.”

To politicians his message is another one: refugees are victims of geo-political games that politicians play. The hunger for power and influence continues to create conflict in many parts of the world, and over and over again civilians are suffering.

"Night. People got together. Families gathered and start sharing stories. Daily experiences differed because the day was spent differently. We miss to share amazing and different daily stories and not stories about the length of the queue for food and its delay, or the queue for taking showers, the queue for getting medical care (basic of course), the queue if not denial of getting out of this fence to buy food, etc.

In short, we are tired of these sad daily experiences/stories. People who have freedom of movement and a dignified life, what do you miss most?"

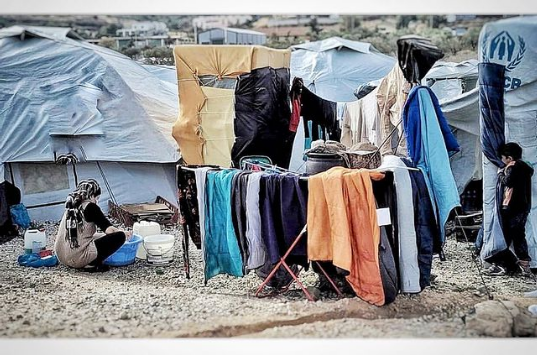

image caption: the_humans_of_moria

Despite the fact that Moria itself has burned to the ground (or maybe exactly for that reason), it has become a symbol for Europe’s failure to provide humanitarian aid to refugees. Sociologist Nikos Xypolytas said in an interview in 2020 about Moria: “It was established in 2015 and the conditions were always atrocious – because it was designed that way.” The inhumane conditions in the Greek camps, but also those along the Balkan route, are a clear signal for those thinking about making their way to Europe to better not even try, because they will end up living in these conditions, sometimes for years. It also sends a message to those who already made it to Europe, letting them know that they are not welcome and should turn back to where they came from. Nikos Xypolytas concludes: “by creating a camp that is by definition overcrowded, a message is sent about the lives of asylum seekers not being worth the same as the lives of European citizens.”

With the failure of a European solution, NGO’s have become essential in providing clothes, food, and medical aid to the camp residents as well as saving people from drowning in the Mediterranean Sea. Nikos Xypolytas explains: “Many NGOs truly help migrants and by doing so they try to undermine EU migration policy – because this is essentially the biggest danger that migrants face. It is not that refugees need help and EU migration policy is providing that help. They need help from migration policy.” Volunteers risk their own safety in this, as they have come under attack from right-wing groups in Greece or have been criminalized by governments.

It takes the burning down of a camp, as the fires in Moria and Lipa has shown, to bring the fate of the humans living there back into the minds of Europeans living in comfort and peace.

"Different place but same struggles

Different year but same living conditions, if not worse

Different Migration pact but same situation, if not worse

Different speeches but same situation, if not worse

Different voices but same resistance

Different approaches but same poor responses

Different meetings but same disappointing decisions.

That was 2020 to us. What to expect in 2021?"

image caption: the_humans_of_moria

News of the suffering of people at the EU’s borders, be it in Greece, Bosnia or on the Mediterranean Sea, are depressing and sometimes overwhelming.

So, if you are wondering what you can do, here are some ways you can help:

What can you do?

DONATE

In the beginning of February, AISU’s Charity Committee is hosting an event to raise awareness for refugees in Greece. You can join the event, tell your friends and family about it, and donate there. The money that is collected helps Amnesty International to advocate for the protection of human rights all over the world. More information will be provided shortly, just follow the Charity Committee’s Instagram to stay up to date!

An organization, which directly helps in the Greek camps, is Because We Carry. This Dutch NGO provides food and clothes for people on Lesbos. On their Instagram account they share snippets of their work and people’s daily life in the camp.

This German NGO Wir Packen’s An is doing the same for migrants in Bosnia. They have already sent 9 truckloads of goods to those living under very harsh conditions in Bosnia after camp Lipa burnt down. Another truck is on its way right now to a camp in Syria. It is a German organization, but of course you can donate from a Dutch bank account.

If you know any more organizations to donate to let us know in the comments or via mail editorial.aisu@gmail.com. We’re happy to extend the list.

DON’T LOOK AWAY AND RAISE AWARENESS

If you can’t spare any money, which is totally understandable, these are other things you can do:

Make sure the people on Lesbos are not forgotten and talk about it with people you know. You can follow Instagram accounts run by people in the camps themselves, such as The Humans of Moria by our interviewee or Now You See Me Moria. Or you can follow this blog, on which the Afghan girl Atifa is keeping a diary of her life on Lesbos. Dutch Photographer Milene van Arendonk shares images of life and people on Lesbos and educates about the situation on her Instagram account by.milene.

Join demonstrations to show solidarity with refugees and demand a change in policy to our politicians. (Just make sure to follow the Covid-19 rules, such as keeping your distance and disinfecting your hands regularly)!

And, if you’re Dutch or German, or of any other nationality where elections are held this year, make sure to vote! In the end, NGO’s can only treat the symptoms of the problem, but for a solution we need political parties in power that care about human rights and for whom the lives of all humans are equally worth – no matter their nationality.

Opmerkingen